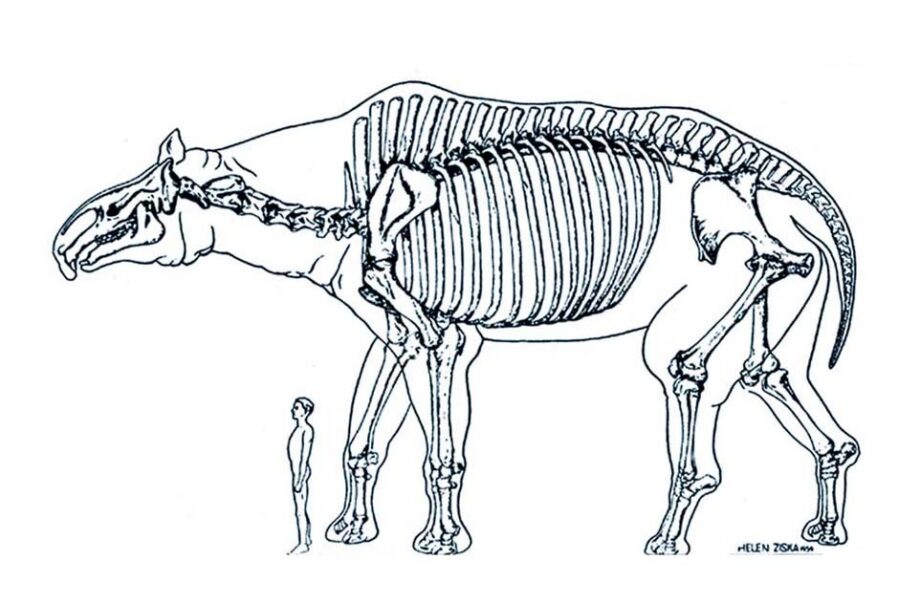

Fossil Rhinoceroses represent an extensive and diverse group of extinct perissodactyls that flourished across multiple continents for over 50 million years. The family Rhinocerotidae first appeared during the Eocene epoch and underwent remarkable evolutionary radiation, producing over 100 recognised species ranging from dog-sized running forms to the massive Paraceratherium, the largest land mammal ever known, standing 5 metres at the shoulder and weighing up to 20 tonnes.

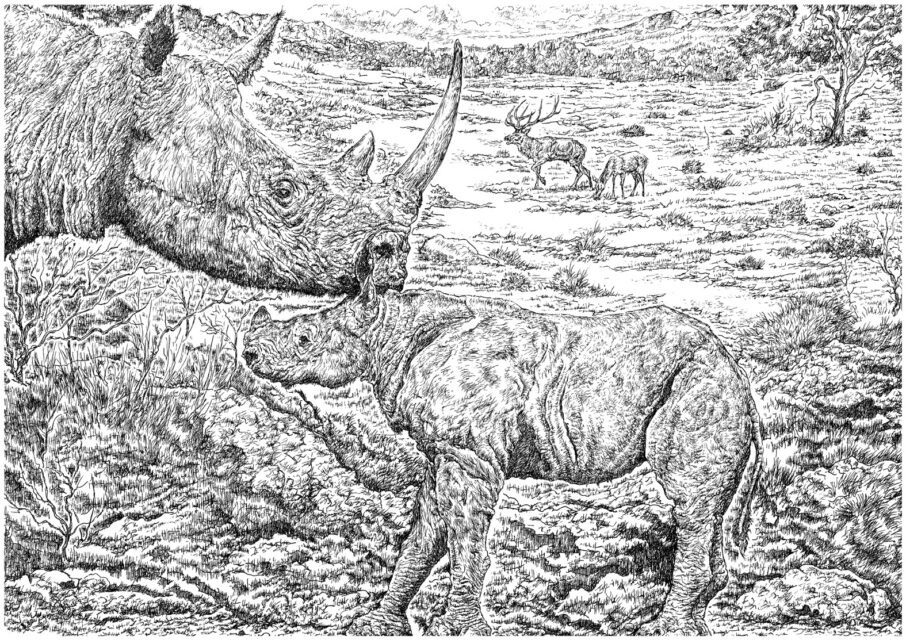

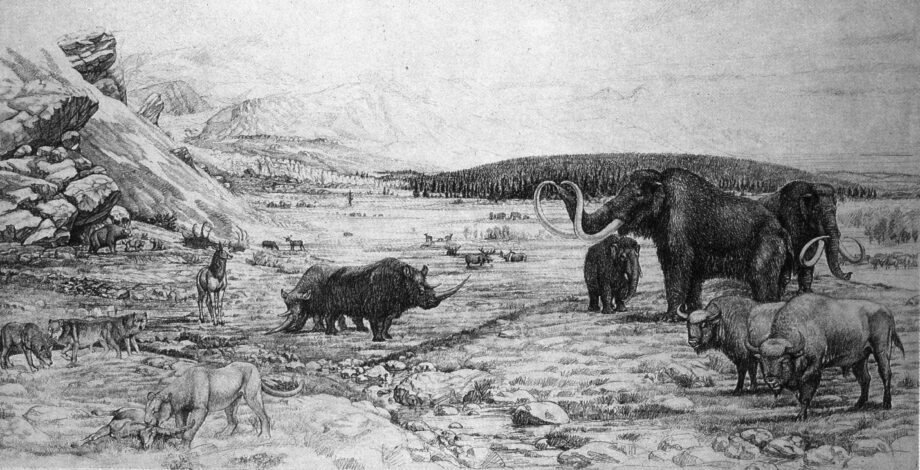

The evolutionary history of rhinoceroses spans three major geological periods. During the Paleogene (Eocene-Oligocene), early rhinocerotoids diversified across North America, Europe, and Asia, including hornless running rhinos like Hyrachyus. The Neogene (Miocene-Pliocene) witnessed peak rhinoceros diversity with numerous browsing and grazing species occupying varied ecological niches. The Quaternary (Pleistocene-Holocene) saw the emergence of cold-adapted woolly rhinos (Coelodonta) alongside the ancestors of modern species.

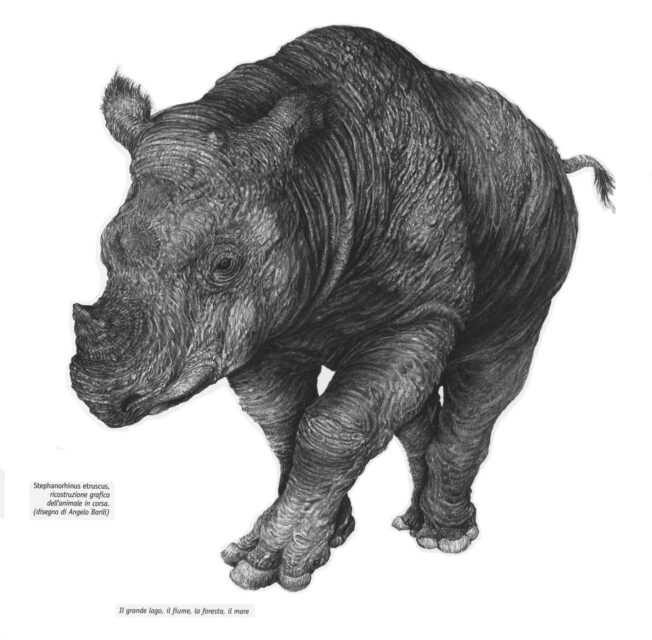

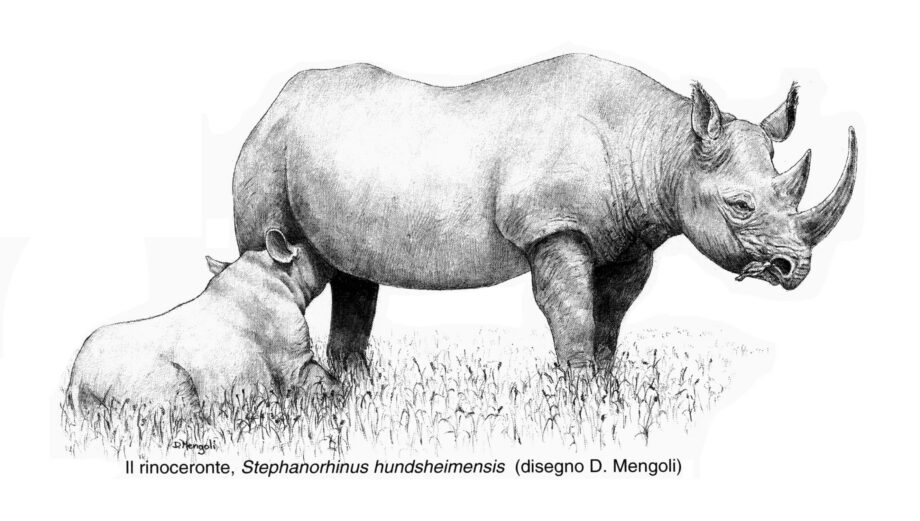

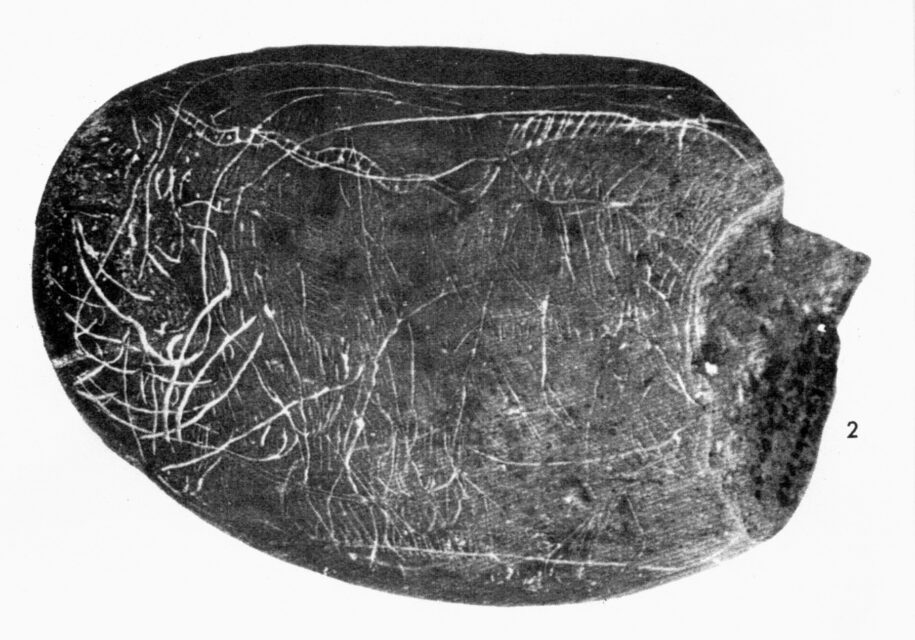

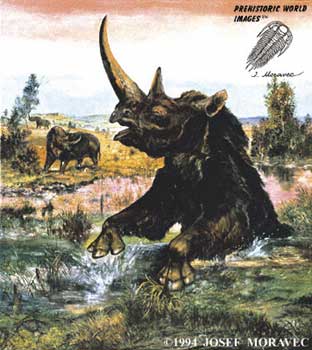

Fossil rhinoceroses exhibited remarkable morphological diversity. While modern rhinos possess one or two horns, many fossil species were hornless, and others bore unusual horn arrangements, including the forehead-mounted horn of Elasmotherium, the “Siberian unicorn”. Body sizes ranged from the 20 kg Mesaceratherium to giant indricotheres. Dental adaptations reflected diverse diets, from leaf-browsing forms with low-crowned teeth to grass-grazing species with high-crowned molars adapted for processing abrasive vegetation.

The geographic distribution of fossil rhinos was far more extensive than today’s remnant populations. Rhinoceroses inhabited North America until 5 million years ago, were widespread across Europe until the late Pleistocene, and dominated Asian megafaunal communities throughout the Cenozoic. Climate change and human hunting pressure during the late Quaternary contributed to the extinction of cold-adapted species like the woolly rhino approximately 14,000 years ago.

Recent palaeontological research has revolutionised our understanding of rhinoceros evolution. Comprehensive bibliographies by Billia (2009) and Billia & Ziegler (2011) catalogue thousands of fossil rhinoceros publications. Molecular studies of ancient DNA from woolly rhino specimens have revealed their relationships to living species, whilst new fossil discoveries continue to fill gaps in the rhinoceros evolutionary tree. These extinct forms provide crucial context for understanding the biology, ecology, and conservation needs of the five critically threatened species surviving today.